Encouraging careers in STEM: outreach at Comberton Village College

5 November 2021

Preventing missed talent in STEM

It is easy to find examples of how science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) have improved people’s lives, especially in the field of medical technology. Careers based on these disciplines can also be deeply satisfying for the individual, with the potential they offer to combine human creativity with analytical thinking to solve important problems.

There are many routes into STEM careers, from more traditional (like Emmy Noether) to less so (like Florence Nightingale), but today one’s career route is strongly influenced by the subjects one must choose at secondary school, typically around the age of just 14. It is difficult to see how a student can make such an important choice in a well-informed way if they have not been shown what careers in STEM exist, let alone what they are like. It is therefore quite probable that talented students who might love a career in a STEM field might never consider doing so, simply because of a lack of exposure.

Springboard was therefore delighted to accept an invitation from Comberton Village College to take part in a careers carousel. The event consisted of a number of stalls, each set up by a different company; and small groups of students had the opportunity to spend 15 minutes with each company to learn about what they do.

Introducing students to technical consultancy

With only 15 minutes to impress eight groups of 12 students each, the race was on to inform and engage. To give the students a good picture of what a career in technical consultancy could be like, we decided they should work through a hypothetical project that we might do at Springboard. The brief:

A pharma company has developed a drug to treat bacterial infections in the retina, and they need to find the best way to deliver that drug. They have come to you to map out the options, and develop one of the concepts into a device.

Armed with two whiteboard pens and several sheets of flipchart paper, we got to work.

Phase 1: brainstorming

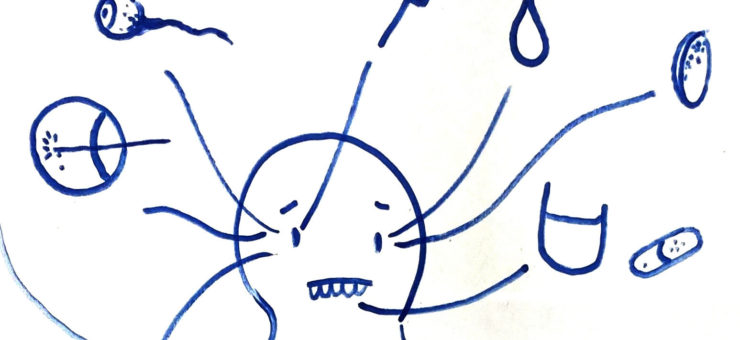

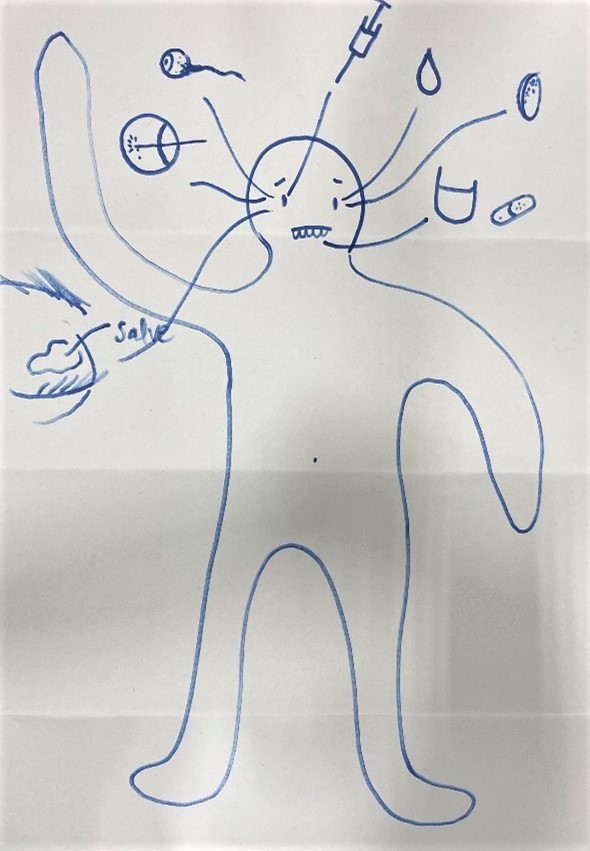

The students, eager to let their imaginations run wild, started to fire ideas at us. “Eye-drops!” one student would exclaim to start off the bidding of ideas. “How about contact lenses?” another would chime in. The ideas were illustrated on the flipchart paper as quickly as they were generated (Figure 1) and spanned an impressive range, from drug-infused contact lenses to salves applied to the eyelid.

If they started to run out of ideas, we sometimes asked how they received a vaccine, which prompted many groups to suggest the drug could be injected into the patient’s arm, and some even proposed what they thought was a preposterous idea: an injection directly into the eye. Invariably, the students were surprised and mildly alarmed to learn that this is in fact a proven method of drug delivery. The hypothetical pharma company decided this is the most promising route for their application, so we moved on to the design phase.

Figure 1: A mind map of the ideas generated by one group of students. The ideas generated by this group included enteral administration, laser ablation, intraocular injection, and drug effusion from a contact lens.

Phase 2: device development

Our next challenge: with just five minutes, how can we show students who have just started their GCSEs how exciting, challenging and satisfying it can be to develop a medical device, without boring or intimidating them? We decided we would use a Socratic approach to try to convey that engineering is essentially iterative, and that science provides powerful guidance for that iterative process.

We therefore started by drawing an eye directly facing an unreasonably large needle, and asked the students: “Is this good enough? Can we do better?”. This prompted another barrage of ideas, including:

- “Make the needle thinner!”

- “Must the injection be through the pupil? Could you inject into the side of the eye instead?”

- “What if the doctor’s hands are shaky? Could you stabilise the needle somehow?”

For each question, we would acknowledge what a good idea it was, and explored some challenges that could ensue. For example, when we asked what might happen if the needle were made invisibly thin, many students realised that it might become too flexible to successfully pierce the tissue; and some even realised that the flow rate would drop dramatically. We would then suggest ways that those challenges could be surmounted, which for that example included:

- Using a more rigid material for the needle (here we would point at some of our materials scientists who would normally advise the team)

- Using a needle with a differently-shaped cross-section (here we would corrugate a sheet of paper and show how much stiffer it became in one direction, and point out some of our mechanical engineers)

- Decreasing the viscosity of the drug, shortening the needle length or increasing the applied pressure (here we jotted down the Hagen-Poiseuille equation to show how physicists can help guide design)

We concluded each session by sharing how we had personally arrived at technical consultancy, and taking their questions.

Conclusions

It was inspiring to see the students’ ingenuity and the variety of ideas they generated, and we think they left with a vision of how the science and maths they will study in school can serve as a foundation to a career in STEM. We hope the students enjoyed the experience as much as we did. Several students approached us after the careers carousel to ask whether we offered work experience placements, which we found encouraging sign and we are planning how we could make this happen. We are very grateful to Comberton Village College for the opportunity.

– Chris Wordsworth and Gabriel Villar